STABLE INCOME BY INVESTING IN SUSTAINABILITY AND ENERGY TRANSITION

As sustainability rises higher and higher on the agenda, healthcare providers face the challenge of investing in replacement or renovation of outdated healthcare facilities and care homes. Demographic developments and changing societal trends are putting great pressure on healthcare providers to invest in expanding capacity. This pressure is reinforced by the requirements of the Paris Agreement to achieve a climate-neutral world by 2050. In this article we discuss the impact that institutional investors can realize by investing in the sustainability and energy transition of Dutch healthcare real estate.

DOUBLE MISMATCH IN SUPPLY

The size of the Dutch healthcare real estate sector is enormous. The total stock in square meters is larger than the combined area of the total retail and office sector in the Netherlands. The healthcare real estate market is traditionally segmented into cure and care. Both sectors have sub-segments. The cure sector consists of first-line care (health centers), second-line care (general hospitals) and third-line care (teaching hospitals). The care sector is segmented into extramural care (care homes) and intramural care (nursing). Despite this large size, there is scarcity. This scarcity has quantitative and qualitative causes. On the one hand, in absolute terms there are too few care facilities and homes available for the growing demand. This shortage leads to waiting lists at nursing facilities, elderly people having to live longer in unsuitable housing and ultimately to a congestion in the flow on the housing market.

On the other hand, the existing supply often no longer satisfies in a qualitative sense. Although the necessary new buildings have been built in recent years, the total stock is, on average, very outdated. TNO estimates that approximately 50% of all healthcare buildings in the Netherlands date from before 1980 (TNO, 2012). Table 1 provides an overview of the gross floor area of healthcare buildings per cluster. Many of these buildings are aesthetically outdated, often suffer from overdue maintenance and have an inefficient layout for residents and care staff. The locations generally no longer meet current requirements in terms of healthy buildings, efficiency and sustainability, and certainly not future (sustainability) requirements. A significant proportion of these buildings are therefore in need of replacement or renovation.

GROWING AND CHANGING DEMAND

In addition to the supply-side issues, the market is also characterized by a growing and changing demand side. The demand for care facilities and care homes is increasing in absolute terms due to the well-known demographic trends. In particular, the double aging of the population plays an important role: not only is the group of elderly people in our country getting larger, the average age is also increasing. The number of people over 65 is expected to increase by 1.3 million over the next 25 years and the number of people over 75 will even triple. The need for intensive care increases exponentially as people get older. On the one hand, this has consequences for staffing levels in the care sector and, on the other, for the type of care facilities required. Demand is also changing in a qualitative sense due to changing social trends.

Most people now in their 70s are much more vital compared to their parents or grandparents. Older people are physically able, and also have the desire, to live at home longer. And that means that the kind of care facilities needed today are very different from the buildings that were built, say, 30 or 40 years ago. A significant proportion of the current supply of care facilities does not meet the needs of care providers and residents in 2022 in qualitative terms. In short, supply and demand are severely imbalanced, both quantitatively and qualitatively. This places great pressure on care providers to make major investments in more and better suited care facilities and housing. As if this were not enough, another storm is looming on the horizon: the aforementioned Paris Agreement to be climate-neutral by 2050. TNO expects that in long-term care alone, investments in sustainability measures will cumulatively amount to between 7.1 and 11.3 billion euros until 2050 (TNO, 2019).

| BVO (× 1 miljoen m2) | Until 1960 | 1960-1969 | 1970-1979 | 1980-1989 | 1990-1999 | From 2000 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitals | 7,2 | 17% | 22% | 31% | 17% | 8% | 5% |

| Nursing homes | 7,1 | 4% | 15% | 28% | 15% | 22% | 16% |

| Care homes | 7 | 9% | 18% | 24% | 22% | 21% | 6% |

| GHZ/GGZ/Youth care | 8 | 12% | 8% | 21% | 18% | 24% | 17% |

| TOTAL | 28,3 |

THE LIMITATION OF BANK FINANCING

Sustainable housing is not the only challenge facing healthcare providers, however. In the latest Barometer Dutch Healthcare 2021, consultant EY foresees several important developments in the healthcare landscape, including the need to make the sector more sustainable, the increasing importance and influence of ICT and innovations, and rising construction costs (EY, 2021). EY further notes that the necessary investments in sustainability also lead to higher costs, without providing direct benefits. Investments to reduce CO2 emissions do not provide an immediate return and only lead to limited savings in energy costs. This places healthcare providers in a precarious situation: on the one hand, an increasing need to invest in staff, new IT systems and strict cost control; and on the other, the need to invest in sustainability measures to meet the ‘net-zero’ requirements of their often outdated buildings by 2050.

Traditionally, standard bank financing has always been the main source of capital for healthcare providers. The Dutch sector banks BNG Bank and NWB Bank – whether or not in combination with the Waarborgfonds voor de Zorgsector – have always played a prominent role in this. However, it is not self-evident that the sector banks are able or willing to fully finance the sustainability and energy transition of the Dutch healthcare sector. This is due in part to the increasingly stringent capital requirements for banks and in part to the enormous scale of the investments required. This is where institutional investors can play a meaningful role.

GROWING ROLE OF INSTITUTIONAL INVESTORS

Partly because of the low capital market interest rates, institutional investors’ allocation to alternative investments is rising. Stable and income-generating assets such as real estate and infrastructure in particular are attracting a great deal of attention. Healthcare real estate is also attracting increasing interest. In 2021, a total of 1.1 billion euros was invested in the Dutch healthcare real estate investment market. That was the third year in a row that the transaction volume exceeded 1 billion euros according to Capital Value, a consultancy in the field of investment property (Capital Value, 2022). Just over a third of the investments were purchased by international investors from Belgium, France and Canada, among others. The remaining investments were made primarily by Dutch institutional and private real estate investment funds.

According to Capital Value, the new-build challenge in the sector remains as large as ever and the investments of the past few years barely compensate for the shortage of care housing. It also recognizes the trend that more and more healthcare institutions are considering not keeping part of their buildings on their balance sheet, but rather exploiting them for the long term. These are often buildings in good locations but where considerable renovation is required to ensure future-proofing. A sale & leaseback transaction between a healthcare provider and an institutional investor (whether or not through an investment fund) can be an interesting solution in this case. The long-term horizon of both healthcare institutions and institutional investors means that there is a stable basis for long-term cooperation.

STABLE REVENUE AND MEASURABLE IMPACT

A sale & leaseback transaction can offer benefits to both parties. The institutional investor receives a stable and inflation-indexed direct income by investing in buildings that are leased for long periods of time (10 – 20 years) to tenants who in many cases qualify as investment grade. In addition to the financial return, there is also a significant social return. In this way, institutional investors make a significant and measurable contribution to making essential buildings more sustainable and thereby reducing CO2 emissions. At the same time, they realize impact by investing in more and more suitable housing for the elderly and expanding the capacity for care providers.

A partnership also has benefits for the healthcare provider. By selling the real estate, hidden reserves can be released. The capital released can be used for investments in ICT and other innovations. Residents and staff are provided with housing and facilities that match current and future requirements. The healthcare institution has certainty about future housing costs and can focus on providing care and well-being to its residents. New or renovated housing also has a measurable impact through lower absenteeism among staff and higher satisfaction among residents.

INVESTMENT ASPECTS OF HEALTHCARE REAL ESTATE

Most institutional investors classify healthcare real estate in the real estate bucket of their strategic asset allocation. Some investors place healthcare real estate because of its social impact (also) in their impact portfolio. Yet other investors also see healthcare real estate as an alternative in their fixed income allocation because of its very long leases and secure income character. The risk of healthcare real estate does not differ materially from that of other segments within the real estate investment market. It should be noted that the investment market for healthcare real estate, despite a rise, is less developed than that for homes, offices or stores.

Two specific risks are explained below: alternative use and tenant risk. The limited alternative use of some healthcare properties applies in particular to very specific buildings in the cure sector. A large hospital is an example. This applies to a much lesser extent to buildings in the care sector and to smaller buildings in the cure sector. Location plays an important role here. A renovated monastery in a green setting can be a very pleasant place to live, but it does not score as well in terms of alternative use. There are more options for a care location in a residential area or on the edge of the center.

A second risk is tenant risk. The tenant risk, or risk of default or bankruptcy of a tenant, varies by specific segment within healthcare. A detailed description of the costing of the Dutch healthcare system is beyond the scope of this article, but in a nutshell, healthcare providers receive a very significant portion of their funding through the government and residents’ mandatory health insurance and co-payment. As such, they can be considered stable counterparties. Although the number of déconfitures is very limited, a healthcare provider is not a government and can still go bankrupt. A traditional public healthcare institution is more likely to be classified as a “systemic institution” by a healthcare insurer than a private provider in the luxury segment. A thorough analysis of the relevant risks and an understanding of the business model of a healthcare provider are therefore necessary.

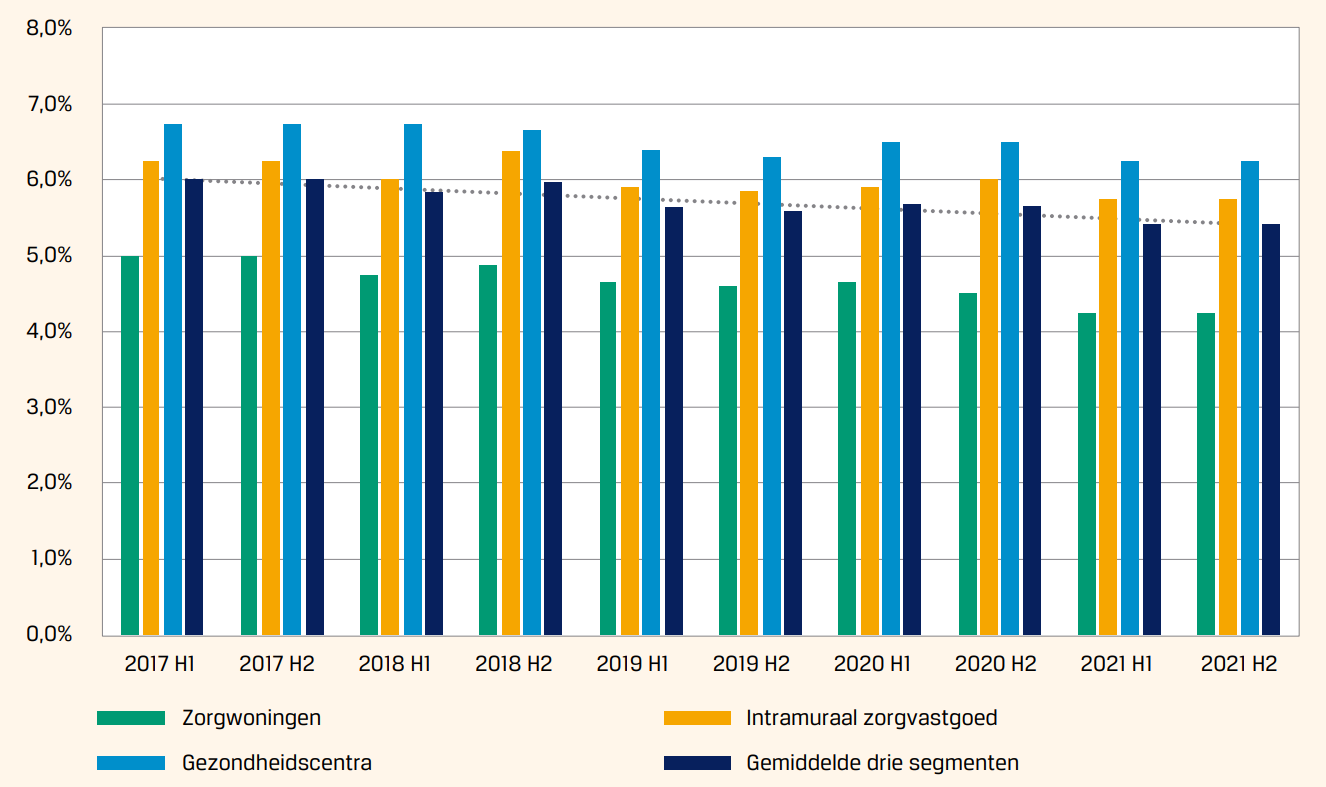

The return on healthcare real estate investments consists of a combination of direct and indirect returns. The indirect return is determined by future value development. The direct return, or gross initial yield of the main segments within the healthcare real estate investment market currently ranges from 3.5% to 5.0% for extramural healthcare housing, from 5.0% to 6.5% for intramural healthcare real estate and from 5.5% to 7.0% for healthcare centers. Since 2017, there has been yield compression of approximately 0.50% to 0.75% (Appraisal Institute Healthcare Real Estate, 2021) (see chart 1).

This yield compression has been partly caused by a general decline in initial yields in the real estate sector due to increased demand for alternative investments, but also appears to be partly a result of a decline in the specific risk premium for healthcare real estate. An investment in equal parts spread over the three segments mentioned above has an expected gross initial return that varies between 4.7% and 6.2%. The net initial yield thus varies between approximately 4.2% and 5.6%. If a long-term inflation rate of 2.1% is used as an approximation for the indirect return, the expected

expected long-term net total return lies between 6.3% and 7.7%.

For a proper assessment of healthcare real estate as an asset class, it is also important to consider its correlations with other real estate segments. The Economic Institute of Construction, in cooperation with MSCI, conducted a study on healthcare real estate in 2015, including correlations with other real estate investments. It should be noted here that the data series on healthcare real estate is still relatively short, so the study dates back 7 years (Economic Institute of Construction, 2015).

The correlation of returns in the cure sector with the All Property Index was 0.64. This varied between 0.58 (with residential properties) and 0.71 (with offices). The correlation of returns in the care sector with the All Property Index was slightly higher at 0.79. This ranged between 0.62 (with Industrial) and 0.79 (with Retail). The correlation of the care property return as a whole with equities (MSCI Netherlands Index) and bonds (JP Morgen Netherlands Index in EUR, 7-10 years) was -0.15 and 0.16, respectively.

CONCLUSION

The size of the Dutch healthcare real estate sector is enormous. Despite this large size, there is scarcity. There are too few care facilities and homes available for the growing demand. One problem is that many existing locations no longer meet the requirements in terms of healthy buildings, efficiency and sustainability. A significant proportion of these buildings are therefore in need of replacement or renovation. The demand for care facilities and care homes is increasing in absolute terms due to the known demographic trends. Supply and demand are strongly out of balance, both quantitatively and qualitatively. This puts great pressure on healthcare providers to make major investments in more and better suited care facilities and housing. Sector banks cannot finance all investments. Institutional investors can play a role here. Healthcare real estate is attracting increasing interest, with a transaction volume of more than EUR 1 billion per year in recent years. A sale & leaseback transaction offers an institutional investor a stable and inflation-indexed direct income. A healthcare provider receives a future-proof building and can focus on its core tasks. In addition to an attractive risk/return ratio, healthcare real estate offers a significant social return and measurable impact.

LITERATURE

- Capital Value. (2022, Januari 11). Transaction volume of healthcare real estate also above €1 billion in 2021. Retrieved from https://www.capitalvalue.nl/nieuws/transactievolume-zorgvastgoed-ook-in-2021-boven-de-1-miljard-euro

- Economisch Instituut voor de Bouw. (2015). Investing in healthcare real estate – Perspective for investors. Amsterdam: Economisch Instituut voor de Bouw.

- EY. (2021). Barometer Dutch Healthcare 2021. Amsterdam: Ernst & Young Accountants LLP.

- Taxatie Instituut Zorgvastgoed. (2021). Marktupdate 2021 H2. Hilversum: TIZV.

- TNO. (2012). Opportunities for energy leap in healthcare (TNO 2012 R10597).

- TNO. (2019). Roadmap for sustainability of real estate in long-term care.